Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

A close-eyed tour of the impact of extraction industries, led by their workers

By Nora Lee Mandel

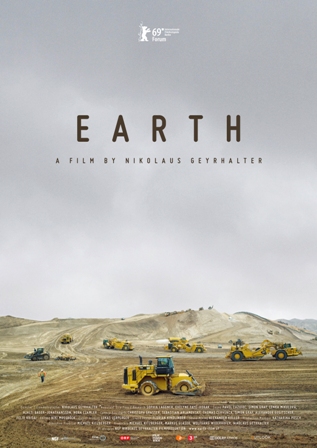

EARTH (ERDE)

Directed and produced by Nikolaus Geyrhalter

Austria. 115 min. Not Rated.

In English, German, Hungarian, Italian, and Spanish with English subtitles

Released by KimStim 1/10/2020

Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s documentary intriguingly positions between the gung-ho admiration of toddler construction vehicle videos or the grown-ups’ History Channel Modern Marvels-type series vs. the apocalyptic warnings of Jennifer Baichwal, Nicholas de Pencier, Edward Burtynsky’s Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018). The big machines are cool to watch – until you are forced to think about the damage they do.

Geyrhalter brings a fresh eye to seven big digs into the earth in Europe and North America and a conversational knack to talk to diverse workers at each site. While asking each about how their machine and the project function elicits responses from quotidian to enthusiastic, their views on their impact on the future of the world are surprisingly varied and insightful.

Each section starts with a beautiful Google Earth view, then Geyrhalter’s own camera gets close to the dirt and the mechanisms to chew it up. To a big rig driver in the San Fernando Valley outskirts of Los Angeles, California, on one American-flag draped vehicle among many, “I move mountains for a living” for yet another suburban development. While a co-worker expresses regret for other jobs that have involved tearing down trees, another sees a primordial struggle as the Earth “fights us every bit of the way, so we have big machines and a lot of horsepower to fight back”, a theme that is repeated throughout.

The dangers of challenging nature are upfront at the Brenner Base Tunnel, under the snow-capped Alps on the Austria/Italy border; the section opens with a tribute to a worker who died on the job, and a priest’s plea to Saint Barbara to protect them. Then the dynamiting continues to great cheers. A young engineer enthusiastically describes the huge specific equipment and technique needed – a gripper clamps into the wall, hydraulic cylinders push it forward, then retract the gripper, move forward 1.7 meters, and extract it again. But he speaks in awe of being the first humans to see these rocks – that get destroyed in a blink of an eye. A female engineer is even more enthusiastic about the project, even though she’s vague about where the rubble goes and shrugs about the need for this new transport route.

At a 16-story tall strip coal mine operation in Gyöngyös, Hungary, workers are eager to describe the fossilized trees they come across, and admire that their crystallization is so hard the bucket teeth on their machines break. But then the work continues. While Zhao Liang’s Behemoth (2015) was a more extensive aesthetic and social look at a large coal mine in China, Geyrhalter adds the warning perspective of time. The local museum curator takes a longer view, back to the cypress swamp forest that used to cover the area over a longer period than humans have ruled. A machine operator sneers at that kind of attitude: “Trees won’t produce energy.” But over his lunch hour, another reflects his shock at a recent visit to a shrunken, millions-year-old glacier, and admits that coal is a big factor.

Two locations reflect on how humans have mined the earth for millennia, but just like the glacier’s melting is speeding up, so is the rate of extraction.

The marble quarry of Carrara, Italy is instantly recognizable. But I never pictured the lovely veined stone for countless sculptures, plazas, and public buildings over the centuries since the Romans being sliced and diced out of a mountain with huge cutting and pushing machines like this. Says the manager, who genuinely loves working at the quarry, but is nevertheless regretful: “Back in the day, you could come back a year after and it looked the same. Today, you won’t recognize it after 15 days.”

At the Riotinto copper mine in Spain, a female metallurgist is absolutely convinced that the environmental impact can be ameliorated because “We don’t want to go back to living in caves, do we? Copper is very important for our lives.” But amidst the dynamite blasting, an archeological dig is going on at the adjacent ancient Roman mine site, whose silver funded the northern expansion of their Empire. The archeologist sees the changes in mining technology in an Ozymandias light, and muses that humans always choose the most violent and rapacious methods.

The centuries old salt mine at Wolfenbüttel in Germany is no longer about extraction, but coping with sloppy storage. Geyrhalter inserts clips from a 1970’s video that optimistically described how safe the mine is – for the storage of nuclear waste. An engineer hopes they can try to minimize the risk from seepage and flood to stabilize the facility. Geyrhalter’s camera pulling back to the radioactivity danger symbol at the entrance is just a hint of the issues of warnings to a million years in the future raised in Michael Madsen’s Into Eternity (2010).

The concluding section veers near cliché about indigenous people’s relationship to the land. But as Geyrhalter follows a Dene First Nations woman to the ruins of Fort McKay, Alberta, Canada, she bitterly describes how her people found themselves “in the heart of the oil sands” where this old open pit mine has poisoned the river and made the fish unsafe to eat. Her hard-earned observation that Mother Nature is retaliating is a rueful summary of this keen tour of human hubris.

Geyrhalter’s Earth (Erde) visually does for the earth’s crust what Victor Kossakovsky’s Aquarela (2018) did for water on the planet, with far more useful explanations. I’m contrite to admit that I’ve somehow missed the Austrian filmmaker’s 25-year oeuvre of documentaries for comparison. But I’ll seek them out now, before the end of earth is nigh that his film soberly predicts is coming soon.

1/10/2020

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online and the Alliance of Women Film Journalists. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Since August 2006, edited versions of most of my reviews of documentaries/indie/foreign films are at Film-Forward; since 2012, festival overviews at FilmFestivalTraveler; and, since 2016, coverage of women-made films at FF2 Media. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2020