Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

A lady from Brooklyn paints Sitting Bull and walks into his last stand

By Nora Lee Mandel

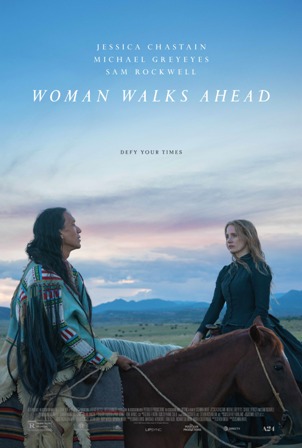

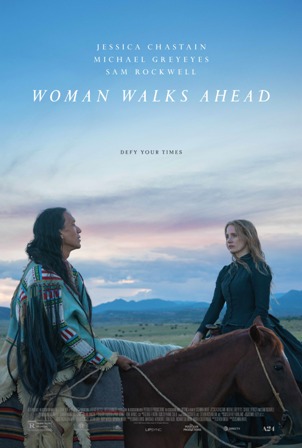

WOMAN WALKS AHEAD

Directed by Susanna White

Produced by Edward Zwick, Marshall Herskovitz, Erika Olde, Richard Solomon, Andrea Calderwood

Written by Steven Knight

Released by A24 on 6/29/2018

USA. 102 min. Rated R

With Jessica Chastain, Michael Greyeyes, Chaske Spencer, Sam Rockwell, Bill Camp, Ciarán Hinds, Makayah Crowfoot, David Midthunder, and Rulan Tangen

Woman Walks Ahead impressively skirts the usual awkwardness of the star with white privilege amidst suffering minorities. In director Susanna White’s period film that pays tribute to a forceful Sitting Bull, the white lady as witness and advocate is a true-life guide to a lesser known tragic history of Native Americans who get full cinematic cultural respect.

The opening credits appear amidst images of George Catlin’s 1830s paintings of free indigenous peoples, like those in the traveling exhibition that inspired Catherine Weldon (Jessica Chastain). She has painted portraits of senators, congressmen, and a vice president, she explains in a voice-over letter to the U.S. government representative in the Dakota Territory, so now widowed in 1889 she intends to paint a similar portrait of Chief Sitting Bull for public display. On the train from New York to the Standing Rock Reservation, Colonel Silas Groves (Sam Rockwell) is suspicious why a woman alone is traveling there: is she a soldier's wife? a missionary? a political agitator? She proclaims she’s “just a painter”. Though Eileen Pollack’s biography Woman Walking Ahead: In Search of Catherine Weldon and Sitting Bull (2002, University of New Mexico Press and its essential 2018 epilogue research update) isn’t credited, left out is that she was a representative of the National Indian Defense Association, based near her home in Brooklyn, that was trying to assist them against the onslaught of federal persecution.

She continues to profess ignorance of any of the political issues the Colonel says are roiling the reservation: getting the Indians to accept the conditions of the Congressional Dawes Act of 1887. They are offered American citizenship in exchange for giving up communal tribal lands for individual allotments -- barren farms, while white settlers got fertile territory. She stubbornly persists, even as she gets mocked in town for wanting to paint Indians, and in her naiveté her luggage is stolen.

Colonel Groves notifies Indian Agent James McLaughlin (Ciarán Hinds) that the War Department is cutting the tribes’ food rations in half “to concentrate the Indian mind” to vote the right way. McLaughlin sarcastically asks his assimilated Lakota wife Susan (Rulan Tangen) how hunger would affect her mind. The Colonel warns about Weldon, while McLaughlin is indignant that she shows up without his approval. They both insist she leave, telling of past Indian atrocities. She counters with her Washington connections.

Her assertion does impress the soldier assigned to escort her. Chaska (Chaske Spencer) turns out to be Sitting Bull’s nephew: “McLaughlin thinks I spy on my uncle for the Agency. But it's the other way around.” Laying out the political pressures between Sitting Bull and the traditionalists counting on the mystical Ghost Dance to protect them from the white man’s bullets and destructive treaties, he offers to bring her to his uncle, if she’ll plead their case to Congress.

Weldon’s negotiations with Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull (charismatic Michael Greyeyes) are a bit reminiscent of the getting to know you between Anna and the King of Siam, as she stubbornly refuses his offer of a horse: “Can't I just walk?” He’s got a sense of humor and wiles to drive a hard bargain to charge her for his portrait. What he should wear for the painting becomes a revealing discussion of the importance of cultural symbolism and the history that each element means to his people because of how each was made. In return, she reveals her unhappy childhood and marriage bound by the restrictions on women. And he gives her the Native American name of the title. These are beautiful scenes in gorgeous Western views; cinematographer Mike Eley is White’s frequent collaborator.

The time Weldon spends with Sitting Bull in his traditional buckskins is seen as betrayal by both his tribe and the Army. When General George Crooke (Bill Camp) arrives to enforce the restrictions, she tries to thwart him by using her own resources to buy supplies. But she’s attacked by townspeople. Sitting Bull’s rival Shell King (David Midthunder) has taken more followers away to the Ghost Dance -- which was such a powerful, last-gasp movement that its recreation should be explained and seen more than it is here.

At a formal dinner at the fort, the bruised Weldon challenges the scheming General Crooke on his hypocrisy, and demands he conduct the vote for the allotments as a true democratic campaign, with speeches and debates. She spurs Sitting Bull to bring his message to his people. In a thrilling set of rallies (in the Lakota language), he challenges the emptiness of a mystical solution and exposes collaborationist elders.

Filmed, ironically, at the same time as the Standing Rock demonstrations against the Dakota Access pipeline, we know history is against the Native Americans. But the degree of the Army’s revenge for the Battle of Little Big Horn is sadly shown realistically horrible.

Weldon returned to Brooklyn a broken woman, and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. While Steven Knight’s script gives Weldon a fictitious back-story, her unique actions in the Dakotas were documented by journalists, government reports, and diarists; her 1890 portrait of Sitting Bull hangs in the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum. Woman Walks Ahead assures that she will no longer be forgotten as someone who tried to help at the zenith of the genocide of Native Americans.

Originally posted 6/29/2018

(Preview at 2018 Tribeca Film Festival, with additional commentary.)

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online and the Alliance of Women Film Journalists. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Since August 2006, edited versions of most of my reviews of documentaries/indie/foreign films are at Film-Forward; since 2012, festival overviews at FilmFestivalTraveler; and, since 2016, coverage of women-made films at FF2 Media. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2020