Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

Cinematic biography serves as a messenger that French Jewish feminist Simone Veil would have a lot to say about Europe today

By Nora Lee Mandel

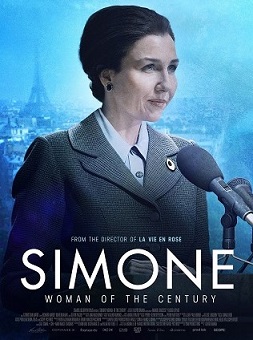

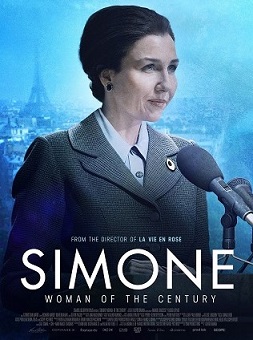

Simone: Woman of the Century (le voyage du siècle)

Directed and Written by Olivier Dahan

Produced by Vivien Aslanian, Romain Le Grand, and Marco Pacchioni

France. In French with English subtitles

139 mins. Not Rated

With: Elsa Zylberstein, Rebecca Marder, Élodie Bouchez, Judith Chemla, Olivier Gourmet, Mathieu Spinosi, and Sylvie Testud

Release by Samuel Goldwyn Films - Opens August 18 in NYC at Angelika and in Los Angeles at Laemmle Royal, and August 25 in Chicago at Wayfarer.

Simone Jacob Veil (1927 – 2017) isn’t known to most Americans, beyond a vague descriptor as a French Jewish feminist. Writer/director Olivier Dahan’s unconventionally presented bio-pic movingly introduces her life story to those who don’t know about her. He specifically keeps relating her political stands against what she views as injustice to her teen-age experiences in concentration camps.

First seen hand writing, and heard narrating, her autobiography in 2006 (published as Une Vie (A Life) in 2009, that I haven’t yet read), Simone (portrayed by Elsa Zylberstein as Simone from 1968) is on vacation with her husband Antoine (portrayed during this same period by Olivier Gourmet), adult children, and grandchildren. Memories seep through in saturated color, starting with childhood summers in Nice with her parents and three older siblings, especially her influential mother Yvonne Jacob (Élodie Bouchez). She describes her Jewish family as thoroughly assimilated into French patriotism: “My father still had faith in the French Republic; he thought it would never abandon us.” (The English subtitles struggle with the French concept of “secularity”, where Americans would just say “non-religious”.) Then gunshots disturb the idyll, and Nazis shout at a long line of Jews in the smokey dark, leaving no ambiguity about her connection to Jewish identity.

A voice cries out “We must resist!”, but the time has shifted to Paris 1974. As Minister of Health, she is deep into strategizing with advisors about how to get Parliament to approve legislation to decriminalize abortion. To the insults by opposition politicians, she is eloquent and emotional about the injustice to young single mothers, and “putting an end to thousands of illegal abortions that mutilate women”. When there’s shouts of “Euthanasia!”, a supporter is shocked: “You know Mrs. Veil’s past and you talk of that?” They go on accusing her of being like a Nazi doctor. At home with her very supportive husband, she reads hate mail and weeps as she recalls what the real Nazis did. The bill passes, women in the street thank her, and Simone remembers her loving mother indulging her stubbornness.

To Paris 1946, where young Simone Jacob (Rebecca Marder portrays Simone 1942-1967) is studying for her political science degree and meets fellow student Antoine Veil (Mathieu Spinosi portrays him 1946-1962), with his secular Jewish family, like hers. It’s not clear where they were during the Holocaust, as Antoine has to interrupt them to stop asking about her parents. She’s having nightmares, but they quickly marry and have babies she names for her dead siblings, like many survivors anxious for a normal life. But by 1948, she’s furious that no one is talking about the collaborators, while witnesses are suppressed and told “to get over it”.

Antoine is excited about a job offer with a new political party and claims “They were all in the Resistance,” without the later sarcasm that would generate. She too gets her degree – but his superiors insist she should support her husband. Her mother, she remembers, told how her husband made her give up her dreams of continuing her science education to become a doctor.

Then in Paris 1975, she’s Health Minister at the groundbreaking of a new children’s hospital, expertly laying the cement: “I used to do this in the camps. It was my job there.” The media finally becomes interested in what she has to say about her past. Back to Stuttgart in 1950, her sister Milou (Judith Chemla) who survived with her, is shocked that she’s accompanying Antoine to work in Germany. For three years with Antoine’s colleagues she has to stifle her opinions and her nightmares. Over family and institutional objections, she determines to become a lawyer, even as she remembers arguing with her father about French law under the Occupation.

Forward again to 1994 when she’s Health Minister. She turns an easy PR visit to a hospital into a private talk with an emaciated AIDS patient that releases her pent-up tears. From this deep empathy, she helps organize an international summit on AIDS. Back to 1957, she embarks on a campaign probably little remembered outside France. As an investigative magistrate, she reveals the atrocious prison conditions, particularly in the racist treatment of Algerians struggling, sometimes violently, against the French government. She moves on to horrible womens’ prisons. At this point, the comparisons to concentration camps are implicit, as she insists on reforms, with little time for her children.

A trip to Israel in 1970 to visit her son working on a kibbutz is awkwardly inserted. The conversation oddly emphasizes her lack of Hebrew and religious beliefs over any affinity she might have for a co-operative with Socialist leanings. Her remembrances drive her for the first time to run in an election, for Member of the European Parliament, where she sees the best hope for peace in Europe into the next century. LePen’s right-wing goons harass her at public events with antisemitic taunts that she challenges back: “You don’t scare me, not a bit, I survived worse than you! You’re pathetic compared to the SS!” Once elected, she makes a point to thank the older Louise Weiss (1893 – 1983), an even more forgotten French Jewish feminist activist, for being her role model.

While still trying to find out what happened to the rest of her family, all the pressures seem to combine to force front-most what she went through in the concentration camps, and she agrees to a TV interview, and a return to Auschwitz, with her children. While Dahan had also met friends she maintained from then, he took the narration of the luck and grit around her survival directly from her memoir. From her arrest in 1944 by French police working for the Gestapo, through her processing, the Death March, to her liberation a year later, the focus is not on the usual sadists, but on her face. She clings to her sister and mother while trying to maintain humanity within barbaric conditions of starvation and exhaustion. We can see the direct connection to her reactions to prisons, ethnic cleansing in ex-Yugoslavia, and other persecutions.

This cinematic biography serves as a messenger that Simone Veil would have a lot to say, and an example to follow, about Europe today, with the return of war, ethno-populist fascism, and the rejection of migrants.

8/18/2023

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

My reviews have appeared on: FF2 Media; Film-Forward; Lilith, FilmFestivalTraveler; and, Alliance of Women Film Journalists and for Jewish film festivals. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2023