Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

More than an image or a legend, history on trial comes alive

By Nora Lee Mandel

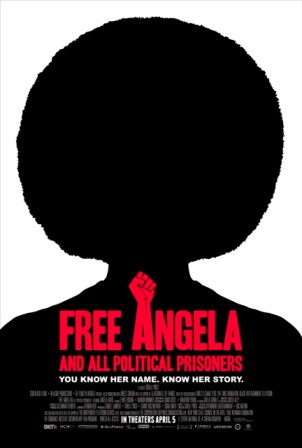

Free Angela and All Political Prisoners

Written and Directed by Shola Lynch

Produced by Carole Lambert, Lynch, Carine Ruszniewski, and Sidra Smith

Released by Codeblack Films/Lionsgate

USA/France. 101 min. Not Rated

Free Angela and All Political Prisoners is a fascinating eye-opener that not only brings history alive, but reverberates into today’s controversies over guns, government surveillance, racial profiling, and media frenzy. Even if you lived through the screaming headlines and TV news about the violent April 1970 siege of a California courthouse that left six dead, including a judge and prosecutor, the months-long woman-hunt, and then lengthy trial of Angela Davis, you will get fresh and insightful perspectives. If she is mostly known to you as an Afro-haired, black-power saluting image on countless posters and T-shirts, you will see a flesh-and-blood person, and how the turmoil of her times turned her into an icon. Key to what makes this absorbing, well-edited and researched documentary different from so many others about the controversies she embodied is that director Shola Lynch got Davis’s participation in extended interviews, as well her friends, relatives, and legal team, plus her permission to access all her FBI files which have never been seen before.

The impression of Davis-the-person was first seen two years ago in her re-discovered, impassioned 1972 jailhouse interview for Swedish television in The Black Power Mix Tape 1967-1975, so it’s disconcerting that she seems to immediately disavow what she said then about growing up in segregated Birmingham and the emotional impact of the 1963 church bombing (so well re-lived in Spike Lee’s 1997 4 Little Girls). Instead, she insists that she had no direct experience with the civil rights movement because she was sponsored for education up north in mostly white high school and college (as seen in many photographs). There she made lifetime friends who are interviewed throughout to add the more personal insights that Davis resists, including wry comments about how much she was a European intellectual after her philosophy graduate studies in Germany, where she says she first learned about the American Black Power movement from afar in the context of global anti-colonial revolution.

Davis is very much the intellectual in describing her early academic career at the University of California, where she was thrilled to follow her mentor Herbert Marcuse and be recruited to teach Marxism, in lectures thronged by thousands of students (seen in campus photos). She is still surprised her hiring generated a McCarthyite backlash in 1969 when then-Governor Ronald Regan challenged the university regents that she’d use her position as a “bully pulpit” for students to join her in the Communist Party, seen in footage of the clamorous meetings, and in an interview with the then-chancellor still sorrowful about the strains on academic freedom. Davis thoughtfully tracks her increasing radicalization after the assassinations, riots, and police attacks on the Black Panther Party: “We were living in a state of siege.” (Coverage of the Panthers staging a legal demonstration with guns about the right to bear arms still seems like an ironic challenge to the NRA.)

The poignant heart of the film is the exploration of her actions and feelings for self-educated, charismatic Black Panther George Jackson, at least as much as Davis permits to be revealed about how she took up his cause as a political prisoner (among others), one of the Soledad Brothers accused of a 1970 prison guard murder. Their visits are among the few re-enactments in the film, mostly shown in distant silhouette, where Davis is portrayed by her niece, actress Eisa Davis, whose mother rallied the world to her sister’s cause and visited in jail while pregnant with her. The closest Angela gets to choking up is recalling him, and one wonders how Oprah would have taken advantage of that opening to delve deeper, especially because that relationship is at the center of the enthralling legal drama that fills the second half in suspenseful detail.

The disastrous take-over of the Marin County Courthouse was led by Jackson’s brother George to demand his freedom, and the FBI found Davis’s signature on the weapons’ registration. Lynch encouraged an archivist to dig up scene-of-the-crime photographs when the assault was happening, that haven’t been seen by the public since they were entered as evidence, taken by photographers who describe grabbing their cameras amidst the chaos, and she interviews the lead FBI agent. Charged with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy, caught on the Most Wanted run, and imprisoned, Davis’s legal fight just starts over her prison conditions and bail. Admitting her difficulty in agreeing to sever her case from the others is the only other time she shows emotion.

Her lawyers are eager and proud to regale their strategy when the case was moved to an all-white jury in San Jose, and the great service of this film is to give legendary nonagenarian civil rights attorney Leo Branton Jr. the legacy opportunity to tell this story, made more poignant and significant because he died shortly after its release. Too bad there’s no additional background provided on him, because he justifiably comes across as bold, brilliant, and as committed to courtroom theatrics in the service of justice as a latter-day Clarence Darrow. He delights in describing his attack on the prosecution’s position that Davis was hopelessly in love with Jackson, starting with having her deliver a stridently feminist opening statement, and then decimating eyewitnesses who couldn’t tell Davis from an Afro’d co-counsel, let alone that she was too visible to have bought those guns. (It’s also surprising to learn that one of her co-counsels was assigned by the Communist Party.) So many outlets covered the trial that the many courtroom drawings virtually become animation. Vividly supplementing the usual TV news clips are the memories of attending journalists, such as Earl Caldwell of The New York Times, and others who read directly from their notes, for a real sense of immediacy of the courtroom atmosphere beyond what even dramatic readings from a transcript would provide, as in Brett Morgen’s Chicago 10 (2008).

But the riveting story just stops with the jury’s quick decision, after the two-year trial, and the Davis family’s fist-pumped celebration (and President Nixon’s comment from his tapes). For a woman who has too often been just an image in politics and popular culture, left out of PBS’s recent Makers: Women Who Make America and Chris Rock’s look at Good Hair (2009), it’s unfortunate to not provide at least a scroll on what she, and the other participants, have done since the trial, and learned from an experience that was personal to them and historic, and now illuminated, for the rest of us.

So, nu: my commentary on the Jewish women in the documentary.

April 29, 2013

#SupportWomenArtistsNow

#InternationalSWANs

#iSWANs

#FF2Media

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews and Commentaries

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews and Commentaries

My reviews have appeared on: Film-Forward; FF2 Media; Lilith, FilmFestivalTraveler; and, Alliance of Women Film Journalists and for Jewish film festivals. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2024