Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

Two films – one gentle, one loud – channel classics to humanize today’s refugees in Europe.

By Nora Lee Mandel

LIMBO

Written and Directed by Ben Sharrock

Produced by Irune Gurtubai and Angus Lamont

UK. 104 min. Rated R

In English and Arabic with English subtitles

With: Amir El-Masry, Vikash Bhai, Ola Orebiyi, Kwabena Ansah, Sidse Babett Knudsen and Kais Nashif

Released by Focus Features on April 30, 2021

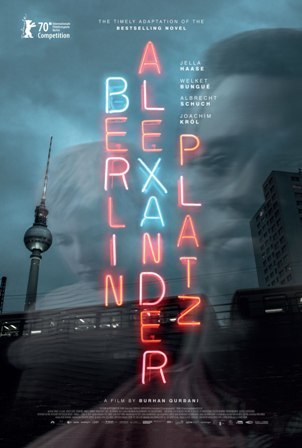

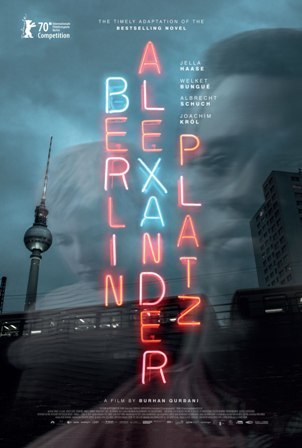

BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ

Directed by Burhan Qurbani

Written by Martin Behnke and Burhan Qurbani, based on novel by Alfred Döblin

Produced by Leif Alexis, Jochen Laube, and Fabian Maubach

Germany. 183 min. Not Rated

In English and Soninke, Portuguese, and German with English subtitles

With: Welket Bungué, Albrecht Schuch, Jella Haase, Joachim Król, and Annabelle Mandeng

Released by Kino Lorber on April 30, 2021 in theaters and virtual cinema through Kino Marquee

Two fiction films released this week in the U.S. by young filmmakers take very different approaches for sensitizing audiences to the traumas, frustrations, and difficult choices facing refugees to Europe. Both aim to individualize “the migrant crisis” with a human face. With his second feature Limbo, Scottish director Ben Sharrock uses a bleak, windy landscape to freeze a young Syrian musician in stasis from playing his family’s traditional oud as he awaits an asylum decision. Syrians are the refugee elite compared to Africans in Berlin Alexanderplatz, where third-time director Afghani-German Burhan Qurbani transfers the plot details and underclass characters in the 1929 German novel to the oppressive options faced today by a striving migrant from Guinea-Bissau.

Limbo is the first movie filmed on the Uist Islands of the Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland. Their desolation and isolation are cinematic manifestations for the PTSD suffered by Omar. (British-Egyptian actor Amir El-Masry has a very expressive face in the frequent close-ups). An unexplained broken arm makes him unable to play his grandfather’s stringed oud, even as he’s haunted by his pride in his past musical success. He takes the instrument case everywhere, as if each day he is tempted to give up and throw it into the surrounding sea. Phone calls with his family, real or imagined, add confusing pressures to send money or visas, or to go home and join the revolution like his older brothers. The fictional set-up matches the tensions and ennui of the Syrian refugee stalled in Karim Aïnouz’s documentary Central Airport THF (Zentralflughafen THF) (2018).

Omar is stuck in a refugee hostel with other men awaiting approval of asylum requests, and each gets to briefly reveal their poignant situation. His Afghani roommate Farhad (Indian actor Vikash Bhai) models his luxurious mustache on Freddie Mercury of Queen. Something of the comic relief, Farhad figures he therefore has the expertise to be Omar’s “agent/manager” for a musical career in England, and helps keep up their hopes for the future. Not so far-fetched, Omar’s dreams are reminiscent of oud player Rahim Alhaj, who left Iraq as a political refugee to the U.S., and 15 years later was named a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts.

The visual and emotional tension is broken by miscommunications over stereotypes from the few locals, with their thick Scottish brogues. There’s humor from ridiculous, but well-meaning “cultural awareness” skits and English lessons by Helga (Sidse Babett Knudsen), to learning slang insults from teasing teens, and additional behavior warnings from an earlier immigrant generation. The tone of these interactions reminds me of such gentle fish-out-of-water classics as Norman Jewison’s <The Russians Are Coming… (1966), Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983), and Christopher Monger’s The Englishman Who Went Up A Hill… (1995). Without contrived slapstick or romance, Limbo is a touching and atmospheric portrait.

The stream-of-consciousness portrait of the Weimar underworld in Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz had gnawed at Qurbani since he’d first read the literary classic in high school (presumably not in the official curriculum). While, like me, others may have the Criterion box set of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 15-hour 1980 television series adaptation on their shelf or bucket list, Qurbani looked afresh at the book for contemporary parallels in the lives of refugees who are not being welcomed as his parents were in 1979. He dynamically adapts the structure and feel of the story with a charismatic cast, brash mise en scène, and noir cinematography.

A drowning in the Mediterranean Sea opens the film under red emergency lights, and haunts perpetual refugee Francis, alongside sacrificial rituals from his barely remembered home in Guinea-Bissau. Portuguese-Guinean actor Welket Bungué carries these flashback burdens through a gripping performance as a migrant with no papers who is gradually transformed from Francis into the violent “Franz” of the novel. The mysterious female narrator through the five-part tale assures the audience he is constantly importuning himself to be good and decent, especially when tempted by prostitutes. But the frustrations from illegally working at an unsafe building site lead him to succumb to the financial and social enticements of the sleazy Reinhold (Albrecht Schuch, scarily riveting into ever more degradations), who recruits at the migrants’ hostel for nefarious purposes.

The first responsibility Francis has as Reinhold’s roommate is to distract and sleep with the women Reinhold seduces and quickly rejects in visceral disgust - “Women are my weakness.” Francis pretty much saves their lives from Reinhold’s psycho-sexual disturbances, while they integrate him as “Franz”. Reinhold brings him into the pill-fueled underground nightlife, especially a bar run by the statuesque Eva (Annabelle Mandeng), who delights in their shared African culture background. The most empowered female in the film, Eva warns Franz he is becoming Reinhold’s “slave”; she’s offended that Reinhold brings him a gorilla outfit for the club’s costume party. Eva later declares to cheers that they are “The New Germany” – the freaks, the Black Amazonians, and the transvestites, like her “guardian angel” Berta (Dutch actor Nils Verkooijen), though Döblin’s 1920’s characters also frequented the gay and trans scene.

Reinhold thinks that for the great favors he’s providing, Franz should do more than cook meals and collect money from his network of migrant African drug dealers. He introduces Franz to his gangster boss Pums (Joachim Kró), who is pleasantly surprised at Franz’s entrepreneurial suggestions for how the business could be run more effectively (shades of The Wire) - plus how to beat the Libyan competition.

The jealous Reinhold convinces reluctant Franz to get more involved in Pums’s suspicious activities, with horrific results. Eva rescues him, and hides him with blonde call girl Mieze (Jella Haase). Even in this love nest idyll, the narrator warns “The hammer comes swinging straight at Franz.” He gets ever more mired in crime because Reinhold keeps promising him the desired path to legality, all migrants’ goal.

The shocking plot elements more and more follow the book’s violent track and its characters’ damaged personalities, as well as the surprisingly hopeful epilogue. But Qurbani adds a galvanizing scene that either seems jarringly borrowed from the American movies he loves or recalls master criminal MacHeath’s cynical anthem “What Keeps Mankind Alive” in Brecht & Weill’s contemporaneous The Threepenny Opera. Franz takes over recruitment for drug sellers at his old migrant hostel with a rousing speech about how this is the way for them to achieve “Their German Dream” of more than a slice of buttered bread.

Certainly the rightists attacking such hostels in Qurbani’s earlier We Are Young. We Are Strong. (Wir sind jung. Wir sind stark.), that I saw at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival, want to block this multicultural future of “The New Germany”. Exhausting and exhilarating, these desperate characters re-birthed from the Weimar Republic and Europe’s colonies won’t stop dreaming, and can’t be forgotten.

April 29, 2021

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

My reviews have appeared on: Film-Forward; FF2 Media; Lilith, FilmFestivalTraveler; and, Alliance of Women Film Journalists and for Jewish film festivals. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

Recommended Films at Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2021