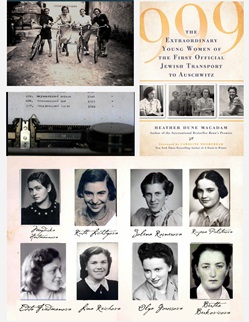

Macadam first helped write the memoir of one of these women, Rena Kornreich Gelissen, published in 1995 as Rena’s Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz. By the 75th anniversary of the first transport to Auschwitz, Macadam had been contacted by other survivors and their families, and realized the need to expand beyond one personal story. From compiling her own list of 22 such women, she reached out to people in Slovakia if they remembered others. Then she found an overlooked, efficiently typed, list of 999 girls’ names in the Yad Vashem archives – as fragile as the now elderly survivors.

Slovakia has rarely been a focus of Holocaust documentaries. Usually survivors’ warm memories of childhoods getting along with non-Jewish neighbors note how everything changed when the Nazis rose to power in Germany, annexed or invaded their Eastern and Western European countries and incited their neighbors into collaboration. But we don’t learn enough about local nationalist Fascist parties that shared Nazi ideology to the ends of gaining independence from empires.

While the current war has resurfaced the controversial role of the Banderites in Ukraine within the “Holocaust of Bullets” through 1941, the female narrator reports on the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party. Led by the priest Jozef Tiso who rose to Prime Minister in 1938, we see the nasty caricatures of its own antisemitic propaganda organs, and hear of the violence of its paramilitary thugs, the Hlinka Guard. Here, the “Aryanization” process was specifically promoted within a Christian imperative, connecting their antisemitism to medieval roots. In September 1941, the legislature passed the oppressive Jewish Codex, and survivors recall how the increasing restrictions on anything Jews could do led to worsening circumstances. Just a few months after the Nazis at the Wannsee Conference established the protocols for the Final Solution, Slovakia had already set up the political and economic conditions, including a detailed household census, for deportation of its 89,000 Jews.

The first Axis partner jumping to participate, Slovakia used what would become a familiar ruse of workers needed in German factories. Macadam ponders if it was genocidal eugenics or did it make this first round-up seem less threatening that the initial group ordered to register were unmarried Jewish women between 16 and 36. (Schadenfreude– when some Christians objected to families being split up, the new Chief of the Jewish Department promised they would be kept together in the future.) The survivors look back at the helplessness of families’ worried responses. Some quickly arranged weddings, some applied for supposed exemptions; only a few were prescient enough or even able to smuggle their teenagers to Hungary, let alone Palestine.

Mostly the Jewish, especially observant, families were anxious to show that they were law-biding when the Hlinka Guard banged on doors to collect even the most rural girls. On March 20, 1942, the young daughters were sent off with suitcases to gathering points in each town. In Danny Abeckaser’s futilely suspenseful docudrama Bardejov (2024, commissioned by philanthropic survivor Emil Fish, Gravitas Ventures), that Slovak town’s aggressively well-informed Jewish Council delays the transport of their 300 girls by faking a typhus outbreak for quarantine. But there’s only a visual implication with the credits that this clever ploy provided any opportunity for a few girls to run away.

The Slovak government paid the Nazis 500 Reichmarks (about $200) to “re-settle” each young Jew, so that list of “volunteers” on the train was necessary bookkeeping. At first singing folk songs and the national anthem that rhapsodized the Tatra Mountains they passed near the Polish border, the girls soon realized there was no food or accommodations before they were marched into cattle cars, as the Hlinka Guards mocked “Dirty Jewish whores!” One woman remembers that date – March 25 – because it was her 19th birthday. Atmospheric reenactments behind the testimonies with music, scenery, and marching feet are ominously effective.

Even as some girls saw that German soldiers took over the transport at the border, they could make out Polish signs to the middle of nowhere, a place called Oświęcim. The shocking cruelties began immediately, by the SS and criminal kapos sent from the Ravensbrück women’s prison, and are intimately described. Macadam found that most conventional oral histories and testimonies leave these out, and she needed to ask survivors more direct, difficult questions. The traumatized young women were pushed naked through bloody snow, around the corpses of Russian POWs whose bullet-torn uniforms they had to scavenge for something to wear.

The Auschwitz camp familiar even from fiction films (clips from Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1960 Kapo are used) was built by this slave labor, joined many weeks later by young Jewish male slaves, and then most sent to build adjacent Birkenau. They had to dangerously demolish existing structures with their bare hands, then start new construction of the bunkhouses, dig swampy ditches through icy water, and more. The Nazi registers didn’t yet tally up women’s deaths from this work; Macadam trusts the survivors as witnesses for who was crushed, fell, or shot when injured.

As the extermination camps took shape and the women’s barracks got more and more crowded, the young women kept their wits about them, and tried to protect those who couldn’t due to the constant illnesses and mental breakdowns. Closely observing which guards were less sadistic or erratic than others, they schemed ways to get assignments that were protected from the elements, were less physically demanding, provided access to extra crumbs of life, where to hide another exhausted/ill girl for hours or a day, and any other small advantage that could gain a girl, her friend, her sister, her cousin, her hometown neighbor, a respite or a way to avoid a selection when the SS raised quotas to fill the crematoria. Even if that meant work at dragging corpses all day.

I was especially attuned to how girls got into “Kanada” – the ironically nicknamed area that allowed the most relative freedom. Expanding as the transports increased from throughout Europe, girls there sorted the belongings of gassed and burned Jews, pulling out valuables that the SS officers would greedily steal. Because that is where my grandmother’s young niece managed to survive, after her family had been starved in a ghetto. On their most wrought days, the girls saw, through the electrified barbed wire fences, their own families arrive from Slovakia. There was nothing they could do to stop the conveyor line to death, let alone that as shaven, boney, filthy, and clothed alike each would be unrecognizable to anyone who had known them from home.

Getting an assignment that allowed a girl to grow out her hair gave her tremendous confidence. One even snuck out postcards to her family that tried to send coded warnings. Others smuggled material to the resistance that led to the explosion of Crematorium IV in 1944. Those who lived were forced along the winter “Death March” where fleeing SS used the girls as human shields against the oncoming Russian and Allied armies. While this agony has been described in other films, it is key that the women remember that those who helped others and had the wherewithal to find anything for sustenance and protection lived longer. As Macadam’s primary guide, nonagenarian Edith Friedman Grosman (#1970), later agonized – did she have some genetic advantage that she survived and her sister Leah didn’t?

While Maya Sarfaty’s Love It Was Not (Ahava Zot Lo Hayta) (2020) expanded on different perspectives of individual women from this group and Noa Aharoni’s Sabotage (2022) includes details on “Marta Bindiger Cige” from Slovakia among the resistance underground, few documentaries have been both close-up and wide-angled in views about women in the Holocaust. Claude Lanzmann admitted to leaving out women’s points of view in Shoah (1985) by releasing Four Sisters as an extra in 2017, where you can hear him interrupt four women’s recounting to get the information he wanted. Closest to Macadam’s accomplishment is the work of Czech filmmaker Lukáš Přibyl, whose Forgotten Transports quartet documented the only survivors from his country, including focuses on women and ”Family Strength”, with specifics on their guards.

Besides Peter Morley’s well-known Kitty: Return to Auschwitz (1979), one of the first I saw, other documentaries that let women survivors talk about their relationships with women in the camps include Carl Leblanc’s Heart of Auschwitz (Le coeur d'Auschwitz) (2010) and Serena Dykman’s Nana (2016); Claire Ferguson’s Destination Unknown (2017) includes several women. Women’s post-war adjustment, including keeping silent for decades, are considered in Chantal Akerman’s video chats with her survivor mother in No Home Movie (2015), Andrew Jacobs’s Four Seasons Lodge (2008), Jon Kean’s After Auschwitz (2017), and the hidden children in Beth Lane’s Unbroken (2013, now streaming on Netflix).

Movingly, the names and numbers matched with black-and-white and color photographs continue through the credits. Macadam’s achievement is a needed tribute to these young female victims and the survivors who have kept their memories alive. Educational for the rest of us.

2/3/2024

On Yom ha Shoah 2025, I learned from a friend that his mother, who was also a neighbor, seems to have been in the next Slovak transport from these 999 in 1942, just one year younger than them. Because her memories were so upsetting, she only gave one documented testimony, in 2019, now in the USHMM Collection, including how essential the friendship among these girls was to their survival as females at Auschwitz, on the Death March, and post-liberation.

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2025