Maven's Nest

Reel Life: Flick Pix

At MoMI’s First Look Fest:

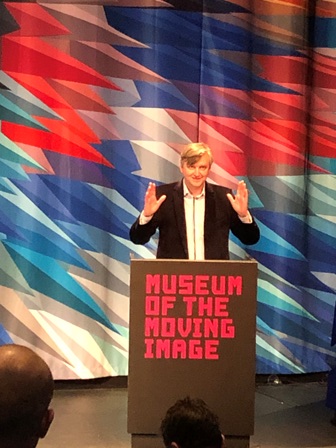

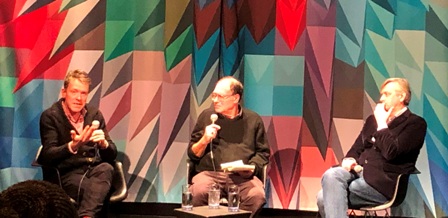

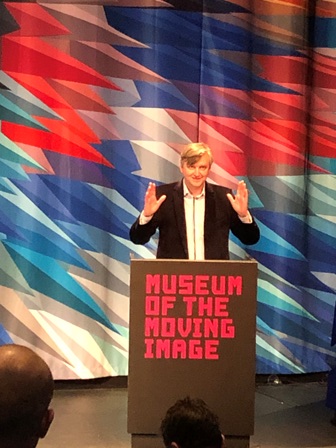

Director Sergei Loznitsa introducing his Opening Night film Donbass; Director Claire Simon with Curator Eric Hynes in between her Closing Night double feature

New Year 2019, Queens Gets First Look at New International Cinema

By Nora Lee Mandel

The 8th Annual First Look Film Festival at the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI), Queens’ own center of cinema education, appreciation, and advancement that appeals to the many different audiences of our diverse county, presented over two weekends, January 11–20, 2019.

The only annual series that the Museum puts together itself, this year’s best-of-international-film-fests was selected by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Chief Curator emeritus David Schwartz, who initiated First Look in 2012 and just retired after 33 years with the Museum. With a slate of all (at least) New York premieres of adventurous, distinctive and sometimes uncategorizable films, First Look also continued, for the fifth year in a row, a special partnership with the French summer Festival International de Cinéma Marseille, now known as the FIDMarseille (aka "The Feed"), whose director Jean-Pierre Rehm hosts several screenings.

Many of the directors attend for introductions and Q & A’s – this year from Russia to France, Israel to Chile. I’ve only attended four years, but the newly compacted schedule over two jam-packed weekends makes it impossible to see all the offerings (though many of the shorts are repeated on the concluding MLK holiday Monday). But this does encourage the directors to attend the weekends festival-style in order by sampling each others’ work and informally interacting with each other.

First Weekend - January 11 – 13

A through theme from Opening Night was the insidiousness of authoritarian systems of control, whether by government, capitalism, or cultural domination. With an emphasis in the first weekend on the former Soviet Union (the Harriman Institute for Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies at Columbia University was a sponsor this year), MoMI followed up on its summer film series Putin’s Russia of over thirty 2000 to 2018 films that riffed and commented on life in contemporary Russia. That series, which I unfortunately missed, included several works by First Look participants, including Sergei Loznitsa, Vitaly Mansky, and Maxim Pozdorovkin, and began to show that manipulation of the truth has been a strategy before Russians promulgated “fake news” on American social media.

Donbass - Opening Night

Director Sergei Loznitsa shrewdly targets several of the dimensions that Vladimir Putin has utilized to punish Ukraine since it turned back to Western democracy, in “the Maidan Revolution” Evgeny Afineevsky also documented in Winter On Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom (2015). With Putin presuming that Moscow street protests were stage managed by the West (somehow personally directed by Hillary Clinton), he seized on using that technique to continue his Make Russia Great Again campaign beyond the military annexation of the Crimean peninsula into Ukraine. Officially denying involvement, Russia stirred up pro-Russian separatists in the eastern region of Donbass, armed them into militias and criminal gangs, and camouflaged Russian military operatives and equipment for an invasion looking like a civil war against the NATO-supported government of Ukraine. Over 10,000 have died; some of the awful impact on children living along the front line can be seen in Simon Lereng Wilmont’s The Distant Barking of Dogs.

Loznitsa is extraordinarily canny in showing how this began insidiously in 2014 – 2015. Born, raised, and educated in Belarus, Kiev, and Moscow, while all were in the former Soviet Union, he is wise to how its history is frequently re-written and “news” is scripted. In talking to friends who were able to leave Dombass, read people’s stories and journals, and interviewing eyewitnesses still living there, they pointed him to how it all played out on YouTube. He realized the videos, shot both by Ukrainians and by so-called Donetsk People’s Republic separatists were used as a weapon to influence people’s perceptions.

Loznitsa explained in the Q & A how he created 13 episodes, linked, like in Buñuel’s (out-of-print) The Phantom of Liberty; seven are direct reenactments of amateur videos. Filmed in a city less than 200 miles from the frontline, using 100 actors with speaking parts (30 professional actors and 70 locals) and 2,000 extras, the behavior captured is amusing, cynical, and horrifying as ethnic tensions are violently exploited. Aided in his ironic documentary styles by his frequent collaborator Romanian cinematographer Oleg Mutu (known internationally for his intimate camera work since 2005 with The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (Moartea domnului Lazarescu)), the selected stories emphasize the corrosion of corruption, from stealing and lying (the head of a maternity clinic denies to a phalanx of furious nurses that he’s not hiding medical supplies that are actually piled up high in his office), to the disintegration of civil society.

The first episode is like a Shakespearean prologue, where actors are getting prepared for their roles and in make-up in a trailer, following instructions from a production assistant. They are led outside, amidst the sounds of a war zone and emote as witnesses on cue into the lens of a TV cameramen in riot police gear. Cameras recording the pitiful sight of families crowded into a bomb shelter are interrupted by a pretty, well-dressed young woman, who looks the very image of an oligarch’s mistress, yells at her disapproving mother to come join her in safety – a tantrum captured on a smartphone. The young woman strides back to the local official in the next episode where revived religious traditions are being stirred into nationalism.

Most viscerally horrific is a telling genocidal episode. A Ukrainian prisoner is tied up in the center of a separatist town, setting off a mob frenzy. That violent scene is later shared among guests’ mobile phones at a raucous wedding of town officials. Another episode is inadvertently a metaphor for the few of us in the Festival’s Opening Night audience who did not understand Russian or Ukrainian language or accents, but were dependent on the English subtitles. A German journalist tries to interview chuckling soldiers at a checkpoint, who can’t give a straight answer to his translator where they are from supposedly. By the time the prologue is repeated as an epilogue, we can really see Russia’s media manipulation. While I read a pro-Russian outlet denigrating this “propaganda movie”, Donbass was Ukraine’s submission to the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film.

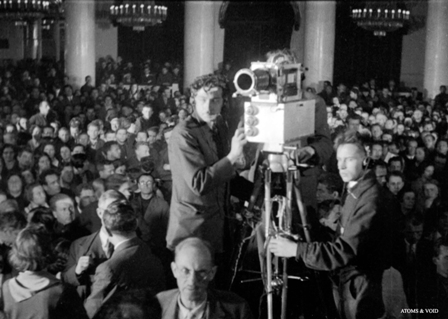

The Trial

The Trial film still/

The Trial film still/  - J Hoberman moderated a discussion between director Sergei Loznitsa (r) and Prof. Jochen Hellbeck

- J Hoberman moderated a discussion between director Sergei Loznitsa (r) and Prof. Jochen Hellbeck

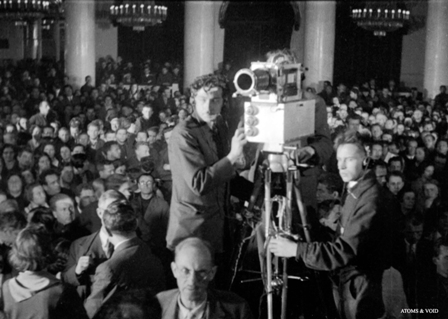

Loznitsa searched for Russia’s propaganda history in the collection of The Russian State Documentary Film and Photo Archive of Krasnogorsk (a center of camera manufacturing) and made an astounding find: a complete film of one of Stalin’s early infamous “show trials”. It’s a misnomer to call this “found footage”, as if it were a random discovery, but this is rare archival film, much as Yael Hersonski found Warsaw Ghetto footage in a Gestapo archive, as revealed in A Film Unfinished (Shtikat Haarchion) (2010).

As amazing as it is to actually see history, Loznitsa is interested in how the lies were staged. The Industrial Party Trial (1930) was directed by Yakov Poselsky (who has directing credits on IMDb from 1916 to 1938), with cinematographer Ivan Belyakov (IMDb documentary credits from 1923 to 1945), using a rare system that embedded sound with the film, though there were very few theaters in Russia that would have been able to screen it. Held in the huge Pillar Hall of the State House of the Unions, different cadres fill the seats each day and turn from the glare of the crew’s lights on them, between November 25 and December 7, 1930. Kafka’s The Trial had only been published posthumously a few years earlier and this is even a couple of years before Joseph Goebbels created Hitler’s Hollywood, producing documentaries and more.

On trial were eight men, mostly engineering professors and academic specialists in metallurgy and textiles, under Professor Leonid Ramzin, declared as leaders of the fictional “Industrial Party” who Stalin wanted as scapegoats for the failure of the industrialization Five-Year Plan. In a script that Loznitsa says Stalin himself marked up, calling him the “co-director”, the trumped-up sabotage charges had to also include (a far-fetched) conspiracy with the French, specifically Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré, who had negotiated with the Czar in an earlier stint in that role. The defendants, prosecutor, and judge all speak into large microphones, so I wonder if this was also broadcast on the radio.

Loznitsa’s edit opens with street scenes of snowy Moscow, with many pedestrians, sled carts, and trolleys. The main “actors” in the production arrive by car to a side entrance. Use of two cameras allowed for close-ups of speakers, court secretaries, and the press row (who don’t seem to need to take notes.) Only one defendant flubs his lines in confusion about which names he’s supposed to detail in his “confession”.

Footage of large night-time processions with torches and Community Party banners is inserted during the recesses, to the tunes of anthems, including the Internationale. After the guilty are all sentenced to death, to enthusiastic cheers in the hall, Loznitsa scrolls his research on what really happened to all the participants. Ironically, several of the defendants made out better during the continuing purges than the judges and prosecutors.

Film critic J. Hoberman moderated a post-film discussion with Loznitsa and Rutgers professor historian Jochen Hellbeck, author of Revolution on My Mind: Writing a Diary Under Stalin. The director insisted that the show trials were theater, staged for propaganda like the TV coverage of “eyewitnesses” in Eastern Ukraine. Dr. Hellbeck interpreted the willing confessions as re-education for the Soviet soul, a revolutionary process I saw illustrated days later in Manhattan, in a rare showing of Fridrikh Ermler’s restored Fragment of an Empire (Oblomok Imperii) (1929) in To Save and Project: The Museum of Modern Art’s International Festival of Film Preservation.

Putin’s Witnesses (Svideteli Putina)

Putin’s Witnesses film still/

Putin’s Witnesses film still/  - Directors Maxim Pozdorovkin (l) and Vitaly Mansky

- Directors Maxim Pozdorovkin (l) and Vitaly Mansky

Documentarian Vitaly Mansky and his camera were present at the creation of the Vladimir Putin dictatorship. Like Ruth Beckermann did in looking back at older video she had filmed herself that became The Waldheim Waltz (Waldheims Walzer), he now narrates his unique footage as a “witness” with the nuanced eye of the perspective of time.

At his family’s New Year’s Eve 2000 celebration, they watch on TV President Boris Yeltsin’s surprise resignation and appointment of little known Deputy Prime Minister Vladimir Putin as Acting President. Mansky, as director of documentaries at what became the last independent TV channel in Russia, decided to make a “Who is Putin?” film through the three months of his first election campaign.

He starts interviewing people who knew Putin growing up in St. Petersburg, including a favorite primary school teacher. So he gets called into Putin’s office and asked why has he been asking around about him? This first up close and personal look at the then 48-year-old gives a few hints of what’s to come in his suspicion of independent media, concern for his image, and attempt to co-opt a journalist with access. Later, Putin calls him in to clarify something he’d been caught on camera saying and to suggest it not be used. (The audience afterwards asked the director if he feels safe living in Latvia.)

The rest of the press follows Putin around as he claims to eschew electioneering, yet visits and presents new projects in every republic across the Russian Federation in his official role as Acting President. Mansky instead went back to talk to former president Yeltsin, obviously in ill health, and his family. Yeltsin sadly admitted that he couldn’t take the stress of the job any more, especially after a series of Fall 1999 terrorist bombings in more than four Russian cities, attacks where Putin rose to reassure the public of their safety. Mansky muses suspiciously that these are still unsolved cases with hundreds killed and wounded that helped convince Russians they needed a strong man to protect them. In the post-screening Q & A, Mansky noted that his wife was instantly suspicious of Putin, because two of her grandparents died in the gulags and she could never support someone who came out of the old KGB system.

During the campaign, Putin never mentions Yeltsin, with whom Mansky spent election night. Even though the winner at 53% was his favored candidate, this doesn’t feel like a victory for him. (Ironically, Yeltsin can’t stand seeing his predecessor Mikhail Gorbachev on the TV.) Curiously, his first telephone call is not to Putin but to a campaign contact of his daughter’s. The climax of Mansky’s footage overlaid with his acidic commentary is the next day at the campaign headquarters. He slows down the film as the camera goes around a big conference table and he identifies each aide. From their positions in the campaign and the first year of Putin’s presidency, he adds “Where are they now?” Almost all are now in the opposition, if they’re still alive. Mansky quit his job rather than continue in any complicity; he sees the Russian nation as a protagonist here “always being a silent witness of its own destiny”.

The post-screening Q & A was moderated by Maxim Pozdorovkin, director of Our New President that was shown at MoMI in July. That amusing as it is troubling collection of TV clips extends Mansky’s perceptions of the Russian president’s media manipulations to the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, divided by apt chapter headings including “Global Reach”, “The Chosen One”, “Informational Pancakes”, “Fake Realities”, and “21st Century Propaganda”. Pozdorovkin even simultaneously translated until the primarily Russian-speaking audience overwhelmed the discussion.

Rojo

Writer/director Benjamin Naishtat slyly demonstrates that the right-wing coup against President Isabel Perón of Argentina on March 24, 1976 – like any fascist take-over of democracy – didn’t occur suddenly without a context of support. While the political news of the restive military is just occasionally heard on the radio, the bourgeoisie in a provincial town are already feeling they can exercise control in their personal interactions over anyone they consider disruptive. By the time of the coup, they are complicit.

Two mysterious scenes set the stage in late 1975. First, in a static look at a suburban house on a quiet street, neighbors walk up to the front door and quickly walk out carrying out a piece of furniture or a decorative item. It does not seem to be an estate sale. Then, in a noisy, crowded restaurant where groups are merrily dining, a regular customer, balding mustachioed lawyer Claudio (Dario Grandinetti, known from Pedro Almodovar films) is waiting for his wife. Until first he, then the whole room, are disturbed by an aggressive stranger (Diego Cremonesi) who demands his table. As first one, then the other man gets the upper hand, the lawyer finally forces the ranting man out, just in time for his wife’s tardy arrival. Normality resumes – until they are attacked in the parking lot.

Both mysteries, and a couple more, come together in Claudio’s law office, in that middle-class suburb, and then way out in the barren desert of the outskirts where secrets can be hidden, by a client (Claudio Martínez Bel) with a shady proposal and confrontations with a very 1970’s Columbo-like detective in a trench coat (Alfredo Castro). People who have leftist or union connections are suddenly leaving (maybe on their own initiative), and there’s even a timely U.S. intervention to save an Argentinean tradition. So teenagers (including Grandinetti’s daughter Laura playing his daughter) can see that if another person, or two, disappear there will only be silence. While at first the smug lawyer has a guilty conscience about what he’s done, he finds he’s not only getting away with it all, but quite successfully.

Each of Naishtat’s three feature films has dealt with violence, history, and memory in Argentina, inspired by his own family history of persecution. The many Spanish-speakers in the audience were well aware the title means “red” -- the color is an ongoing visual motif, in 1970’s styles, an eclipse, the “Red Peril” the right-wingers saw everywhere, and the blood starting to be spilled on screen, and in the country. Rojo can be seen as an alarming harbinger or entertaining parable of the dictatorship’s nine-years-long “Dirty War”, let alone any society that tolerates fascism. Distrib Film US is opening the film in NYC theaters on July 12, on July 19 in Los Angeles, followed by other cities.

The Crosses (Las Cruces) (2nd Weekend)

“The White Crosses” film still/

“The White Crosses” film still/  co-directors Teresa Arredondo & Carlos Vásquez

co-directors Teresa Arredondo & Carlos Vásquez

Just two days after General Augusto Pinochet began a brutal military dictatorship in Chile with a coup d’etat on September 11, 1973, 19 people in the small southern town of Laja were rounded up at work, brought to the police station, and were never seen again. Forty years later the official story of what happened changed.

Living in Santiago, Chile, co-directors by Teresa Arredondo & Carlos Vásquez five years ago read about this unique crack in a fraught history. In cooperation with the families of the disappeared, they movingly track where the past, memory, conscience, and grief come together in the very specific locales of one community that looks like it hasn’t changed – except for the crosses.

Outside of town, the forest is still being cut down to feed the big paper and pulp mill of Compañía Manufacturera de Papeles y Cartones (CMPC) and products are shipped out on the trains that click-clack through. The company is still the major employer, as we see a long line of men carry their lunch boxes to work, and people are afraid to go up against the powerful family that owns it. Police reports from September 1973, with some conflicting facts, appear on screen, read by named family members. The Carabiniers tell of a list of names of union activists sent over from the factory, and their captain’s orders to pick them up and bring them back to the busy police station. The camera follows the road the company bus would have taken them. The policemen cite instructions to take the prisoners to a bigger jail in a nearby city, and the camera shows the streets around that station, too, where the families went asking for their disappeared, to no avail.

But then there are other reports shown on screen and read aloud, and the camera follows the rural roads to those described locations. A farmer chasing his runaway horse complains that dogs have found bodies buried in a shallow grave in a private forest. Then the bodies are gone, and there is no investigation. Years later, bodies are found in the outskirts of the town’s cemetery, but an investigation is inconclusive, and the families keep putting up crosses with the names and photos of their disappeared. In 2013, one policeman, and then another, testify in detail what really happened. They just followed orders, and the camera follows where they went first with the prisoners, then with bags of lime and bodies. The grisly testimony sounds like how Hitler’s Einsatzgruppen death squads operated, but those perpetrators never confessed.

Inspired by the styles of the Holocaust films of Claude Lanzmann and how Deborah Stratman portrayed Native American genocide in The Illinois Parables (2016), the directors focus their 16mm cameras on the local landscape and structures. Then the families are seen setting up memorial crosses and talking of blocking the company’s logging machines from running them over. The touched and thoughtful audience included Chileans and those from other countries who suffered under a military dictatorship, including Greece.

The Disappeared (Hane’elam)

The Disappeared film still ©/ co-directors Gilad Baram and Adam Kaplan

The Disappeared film still ©/ co-directors Gilad Baram and Adam Kaplan

In this hypnotically compelling documentary, government censorship is as viscerally visible as a completely redacted Freedom of Information Form. What officially cannot be seen can only be heard through voices, sound effects, and music. And it’s a great story to pack into 46 minutes.

Co-director Gilad Baram’s required service in the Israel Defense Forces in 2000 was with the Spokesperson’s Film Unit, which produces PR material for the Army and attracts many Israelis from throughout the film industry for their reserve duty. As coincidentally told by writer Etgar Keret in Stephane Kaas’s bio-doc Based On A True Story screening the same week as First Look at the Jewish Museum’s New York Jewish Film Festival at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, the Israeli Army was very concerned about the rising number of soldier suicides, with his best friend’s added to the statistics. The authorities approved a film called The Disappeared to alert people about the warning signs for suicide prevention.

From their new base in Berlin, Baram and his Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design classmate Adam Kaplan researched the making of the film for over a year and located parts of the script, set photos, and composer Eldad Lidor’s score. But they chose to do the almost 30 interviews in Israel with cast and crew as audio only, which probably freed up frankness while glaringly emphasizing what has been banned. First over white blank screen are background remembrances on how the film grew into a major romantic action production with over $1 million budget, much more than standard even for intended wide domestic theatrical release. The unit head/writer-director Michael Yohay reads the opening set-up, then other voices start chiming in on how the Army made any resources available to him, including helicopters, tanks, hundreds of extras at multiple locations around the country, and even access to a top-secret missile base. Baram was his location manager through the whole production.

The interviewed participants sometimes have amusingly conflicting perspectives on how the plot developed and grew in scope. They include many professionals in the Israeli film industry, such as cinematographer/director Dror Moreh (The Gatekeepers (Shom'ray Ha'saf)); the main cast members, pre-stardom Lior Ashkenazi (Footnote (Hearat Shulayim) and actress Nataly Attiya. Other actors include Roy Assaf (Jaffa) and Alon Dahan (A Matter of Size (Sipur Gadol), producer Marek Rozenbaum (Seven Minutes in Heaven (Sheva Dakot Be’gan Eden), and others who have gone on to such careers as writer and editor.

The screen blacks out completely during background discussions, then looks like scratchy video tape during specific scenes, perhaps like the bootleg copy the co-directors were eventually invited to privately view. (I was surprised the young directors knew about VCR quirks, though they never heard of the U.S. government’s suppression for over 40 years of John Huston’s World War II PTSD documentary Let There Be Light.) The unseen interviewees are also like how the participants in Orson Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind are heard in Morgan Neville’s documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead. The directors noted that international audiences seeing this sub-titled version with the Hebrew-speaking voices match how Israelis watch non-Israeli films.

There’s an additional external irony. A former IDF Spokesperson who is now Israel’s conservative Culture Minister, Miri Regev last year criticized Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot, also starring Lior Ashkenazi, as “anti-Israel” -- without seeing it. She probably had a hand in the continued censorship of the original version of The Disappeared. (So, nu: my identification of the Israeli women.)

The Pluto Moment (Ming wang xing shi ke)

Two films from China, with different approaches, show that traditional rural culture manages to survive outside Communist Party censors, and attracted Chinese-speaking audience.

With The Pluto Moment, at first I thought I was watching an imitation of another Hong Sang-soo film where the problems of a young Korean filmmaker are central. But writer/director Ming Zhang just starts out with a similar premise of big city filmmaker Wang Zhun (Wang Xuebing) bringing his personal issues with him on location along with his crew, and the references to his past relationships mostly become running gags.

Instead, this is a quest story, as the filmmaker is convinced that he must include “The Tale of Darkness” in his movie to inspire his script, and to preserve this oral epic story. Much as Ming Zhang himself some years ago went back to his home region, the filmmaker travels to Wu Mountain and deep into the south central province of Hubei to find this “living epic” of 5,000 lines performed in the traditional manner that tells the history of the Han Chinese people from the birth of Heaven and Earth, the creation of humans, on through the 15th century Ming Dynasty.

But just as the story of the universe and humanity doesn’t go smoothly, things keep going wrong in this microcosm. The urbanites miss rides, have to hike further into the forest, face the natural elements of cold, rain, and bugs, and have to stay with the peasants, sharing their food and living conditions. (There’s some side stories at each stop on the way.) The producer/fixer with political connections assures them what they really need is for a villager to die for them to capture a funeral – but even then it amusingly becomes an issue of finding an authentic funeral experience.

Many locals are incorporated into the film shoot at each of these gatherings, as “the nocturnal song” must be sung at night – so the title is a metaphor for when it’s time for the light to meet the night, and the planets become visible. Their quest ruefully discovers that Chinese pop culture is reaching ever farther into the hinterland. Ming Zhang points out that he accepts the necessary censorship of working within the Chinese system, so presumably the government approves that the film shows Han culture is being preserved, even as much is being lost.

Turtle Rock

Turtle Rock is a natural landmark near director Xiao Xiao’s childhood home village of Tuan Yu Yan in Hunan Province, in south central China. Bamboo forests cover the surrounding mountains that look beautiful in each season of the year, through wind, mist, rain and snow. This Chinese painting scroll aesthetic makes his debut film more than an anthropological study of the ten families who have lived there for generations, compared to Safi Faye’s colorful ethnographic Fad’jal (1979) filmed in her home village in Senegal, a restored print I saw days later in Manhattan in To Save and Project: The Museum of Modern Art’s International Festival of Film Preservation.

His black-and-white cinematography emphasizes this portrait of his relatives living peacefully within their environment and following traditional Buddhism will soon be history. The buzzing sound of a saw mill encroaches through the valley, overpowering the sounds of nature. Villagers young enough to do this hard work use traditional logging and carrying methods to bring downed trees to feed the noisy machines.

Like many rural Chinese villages, the residents are primarily elderly caring for beloved grandchildren. Bus stops (with posters from the local legal authority) link them to the bigger towns where the younger generation has moved on for education or jobs and come back for visits; the director hopes to follow-up those for his next project. Filmed in 2015 – 2016, this feels like our last chance to watch this daily life over a year. An observational documentary of nature (a lot of spiders weave webs) and busy people with no interviews (and little sense of individual personalities), old women take the children climbing on pilgrimages to bodhisattva shrines, probably in hope that they will remember the overgrown paths to reach them with the ritual incense to burn with what prayers to say.

Uppland

Uppland film still/

Uppland film still/  - co-directors Doherty and Lawrenson

- co-directors Doherty and Lawrenson

The impact of colonial capitalism, particularly on Africa, continued, but gets forgotten.

Irish architect Killian Doherty was first curious about the incongruity of a “new town” in the Liberian highlands with modernist Scandinavian design. As a specialist in the “exploration of fragmented sites, settlements and cities at specific thresholds of racial, ethnic or religious conflict”, he took along Scottish filmmaker Edward Lawrenson, whose earlier film was about his home town built for miners in the 1950s, to document the architectural anomaly. They found there was an untold story behind, under, and around the rusted ruins once called “New Yekepa”.

Filmed like an ironic Heinz Emigholz architectural tour, the town was originally set up in 1955 for the primarily Swedish employees of Lamco, the Liberian-American-Swedish Mining Company, when iron ore was discovered in the mountains, and a big mining operation commenced. There are interviews (in Sweden, with souvenir African masks decorating their walls) and archival photos and home movies of what a good time the employees had working, living, and playing there (there’s many images of when the now overgrown swimming pool was the center of fun). The filmmakers ask around and find a few older Liberians who had menial jobs there and do have fond memories despite the racism and classism.

But there are intriguing hints of “Old Yekepa”, and it takes awhile to find a Mano tribal elder who is willing to show them. Traveling towards the mountain, the elder points to a barren landscape and moves around the overgrown bush, viscerally remembering who lived where and did what. While I’ve seen Holocaust and other genocide documentaries where witnesses similarly recall a vanished past, the static camerawork treats these spaces like the architectural documentation. From this site, they can now see the abandoned iron mine that stripped a mountain and littered the environment with broken extractors and polluted sludge, a mountain that was central to local spirituality and ethnic identity through oral histories of sustainable hunting.

So where did the people go from their ancient land? After over 60 years of broken promises, a ruined mountain, and dislocated culture, the people eventually trust the filmmakers enough to reveal the real story of the Scottish geologist who descended in a helicopter with paper promises and manipulations of a myth. On their own, with no help or resources, these folks had to eke out their own new “New Yekepa”. While The Sustainable Development Institute is working with the displaced tribe on their land rights, the “architectural” images of each place are strong enough to give the viewer a physical reaction. (Grasshopper does non-theatrical distribution of this half-hour short.)

Going South (2nd Weekend)

Going South poster/

Going South poster/  - moderator critic Leo Goldsmith with Dominic Gagnon

- moderator critic Leo Goldsmith with Dominic Gagnon

Québécois collage editor Dominic Gagnon mashes together thematic series of YouTube compilations that have been accused of colonial cultural appropriation. Asserting that these are by definition of the medium in the public domain, he does exploit amateurs (especially minors) who use YouTube with their possible exaggeration, deception, distortion, and disinformation for attention, gratification, and emotional manipulation, all for the potential profitable sponsorship of their channels for which they pitiably plead “Click on ‘Like Me’!”

Of The North, Part 1 of his current tetralogy on the cardinal points of the internet, was shown at the fifth annual First Look Festival in January 2016. But that was already a version redacted of the videos that offended indigenous northerners by repeating stereotyped images, clips that he claimed were filmed and/or posted by locals, though that contradicts his own description of his selections as representative of our “post-truth” era.

As Part 2, Going South refers both to warmer climes and the American slang phrase of letting loose. Clips of drunken spring breakers are cheap shots for slapstick laughs. The Flat Earthers online have already been revealed in their own documentary by Daniel J. Clark, Behind The Curve. There’s also a couple of ringers, the U.S. astronauts officially downloading from the International Space Station and a citizen journalist recording riot police cracking down on a demonstration in an unidentified Asian city. Gagnon does not seem interested in these powers of YouTube, like Sergei Loznitsa did in the Opening Night Donbass or Peter Snowdon’s edit of “Arab Spring” YouTube videos into one narrative as The Uprising (2013).

Gagnon’s inclusion of several sequences from Grand Theft Auto V and an app that generated an animated full bore Santa battle like Game of Thrones added to the full audience of millennials appreciating this scattered compilation of Other People’s Work a lot more than I did.

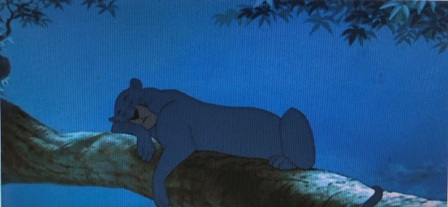

The Pure Necessity (Die Reine Notwendigkeit)

The Walt Disney Company has been the ultimate perpetrator of global capitalist culture for decades and is a zealous protector of its copyrights. Belgian artist David Claerbout takes on the Mouse House to challenge copyright law and appropriate their classic images by disassembling and re-assembling them.

His target was The Jungle Book (1967), which he remembers first seeing in a movie theater when he was about six years old. (The original director was Wolfgang Reitherman, one of Disney’s “Nine Old Men” of their classic animation.) Over three years, with a team of eight animators, Claerbout frame-by-frame removed all narration, dialogue, dancing, and other anthropomorphic features from the animals. Their first iteration was black-and-white drawings for an art exhibition, then they developed the color, hour-long film in the festival to be viewed specifically in a theater. Even the Disney background was separately copyrighted as a work of art, so he and his team had to re-draw enough by hand to satisfy his lawyers. Claerbout feels he has appropriated some cultural aspects, so the entire animation can be considered close to the original, but new.

His new version is a more like an educational nature animation, as if the audience is watching a bear, panther, monkeys, and python have normal behaviors and body movements (though in this African jungle the bear seems inauthentic). Still charming, this film could have been shown to a family audience, and I encourage film festivals to have a family film. (Last year First Look did have Solveig Melkeraaen’s wonderful documentary Tongue Cutters.)

Disney may have conditioned even small folks already to expect animated animals to talk and sing, let alone that the company even anthropomorphizes wildlife in the narrations for its nonfiction “Disneynature” films. But this “pure version” lets the audience separately appreciate the animators’ attention to detail from close observation of flora and fauna. This pure version of The Jungle Book is wonderful!

Second Weekend - January 18 – 21

Reviews forthcoming!

updated 6/11/2019

Nora Lee Mandel is a member of New York Film Critics Online and the Alliance of Women Film Journalists. Her reviews are counted in the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter:

Complete Index to Nora Lee Mandel's Movie Reviews

Since August 2006, edited versions of most of my reviews of documentaries/indie/foreign films are at Film-Forward; since 2012, festival overviews at FilmFestivalTraveler, and, since 2016, coverage of women-made films at FF2 Media. Shorter versions of my older reviews are at IMDb's comments, where non-English-language films are listed by their native titles.

To the Mandel Maven's Nest Reel Life: Flick Pix

Copyright © 2019

The Trial film still/

The Trial film still/  - J Hoberman moderated a discussion between director Sergei Loznitsa (r) and Prof. Jochen Hellbeck

- J Hoberman moderated a discussion between director Sergei Loznitsa (r) and Prof. Jochen Hellbeck

Putin’s Witnesses film still/

Putin’s Witnesses film still/  - Directors Maxim Pozdorovkin (l) and Vitaly Mansky

- Directors Maxim Pozdorovkin (l) and Vitaly Mansky

“The White Crosses” film still/

“The White Crosses” film still/  co-directors Teresa Arredondo & Carlos Vásquez

co-directors Teresa Arredondo & Carlos Vásquez

The Disappeared film still ©/ co-directors Gilad Baram and Adam Kaplan

The Disappeared film still ©/ co-directors Gilad Baram and Adam Kaplan

Uppland film still/

Uppland film still/  - co-directors Doherty and Lawrenson

- co-directors Doherty and Lawrenson

Going South poster/

Going South poster/  - moderator critic Leo Goldsmith with Dominic Gagnon

- moderator critic Leo Goldsmith with Dominic Gagnon